I alone remember. And if I don’t tell you, children, everything that was and everything we knew, all will be lost.

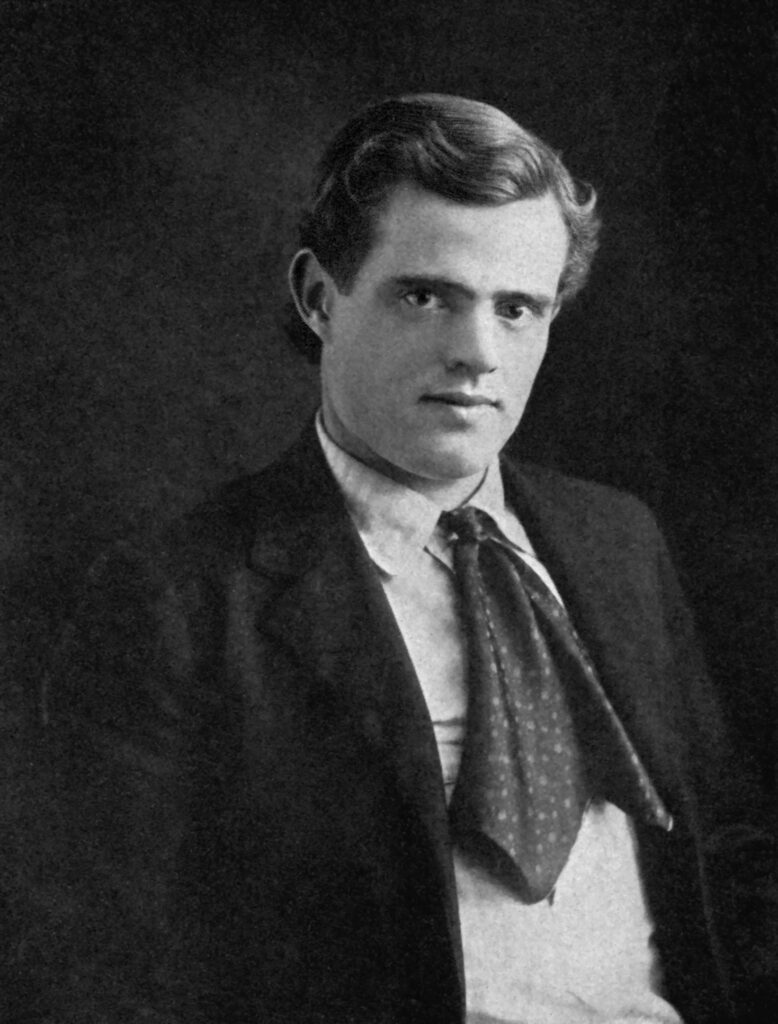

Jack London (1867–1916) was a prolific American writer. He’s best known for adventure novels like “The Call of the Wild” and “White Fang,” but his vast work also addressed social issues.

“The Scarlet Plague,” a short novel written in 1912, is notable for being one of the first post-apocalyptic novels in modern literature.

The historical references that likely inspired the author were the plague and cholera epidemics (as depicted in the stories of Boccaccio and Defoe). These occurred during periods when medicine was still in its infancy and lacked effective remedies against diseases. Interestingly, the Spanish flu pandemic itself emerged after London had written this story (1918–19).

The Story

Set in 2073, exactly 70 years after a catastrophic epidemic—the scarlet plague—decimated humanity, the story depicts a world where survivors have regressed to a primitive state.

Professor James Howard Smith narrates the events leading to this outcome, aiming to pass on the memory of the plague and its consequences to future generations.

The scarlet plague, whose clinical and epidemiological characteristics the author doesn’t elaborate on, was marked by an extremely high transmission rate and mortality. Its severe virulence and the inability to mount an effective response led to widespread panic and chaos.

It was a frightful epidemic. People were dying like flies. The disease killed within minutes and the infection spread like wildfire. People were seized by desperate panic, and everything descended into chaos.

Cities crumble, infrastructure collapses, and the few survivors gather in small, isolated communities. They revert to a state of barbarism where civil achievements and medical knowledge fade into obscurity. Centuries of scientific discoveries vanish, lost to time.

Everything has been lost. Not just civilization, but everything that was part of it. Science, medicine, all knowledge… nothing remains anymore

Healthcare systems were the first to collapse, unable to respond to the pandemic and lacking the resilience to survive it. Hospitals became viewed more as sources of contagion than places of treatment.

The cities emptied out. Hospitals were abandoned, no one had the courage to approach the sick. The government dissolved and people sought refuge in nature, far from the contagion

Doctors, in particular, were astounded by the speed and lethality of the unknown disease. Unable to identify its cause, they tragically became victims themselves.

“Doctors were brave, some of them died while trying to treat others, but nothing could stop the scarlet plague. There was no cure, there was no hope.

The post-pandemic state of barbarism, along with the loss of medical knowledge and basic health norms, demonstrates the fragility of scientific achievements and hygiene practices we often take for granted. This stark reality underscores the critical importance of careful public health management.

Without the knowledge of the past, men have returned to barbarism, no longer caring about hygiene or medicine. We live like beasts, devoid of the most basic standards of cleanliness

Ancient and Modern Pandemics

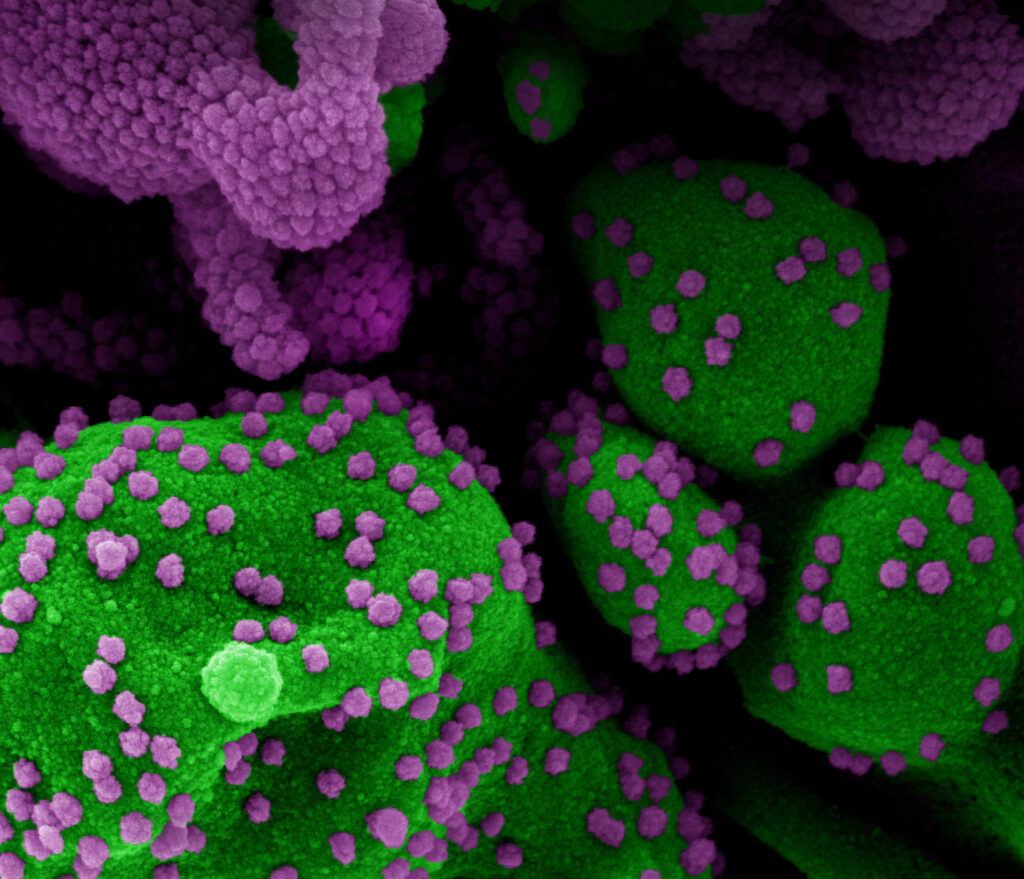

Jack London’s “The Scarlet Plague” demonstrates a remarkable foresight that echoes with our recent experience of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the coronavirus certainly exhibited less virulence than London’s fictional “scarlet plague,” the parallels between the imagined events and our lived reality in 2020 are both striking and thought-provoking.

London’s prescient narrative serves as a reminder of how literature can sometimes anticipate future challenges, offering valuable insights into human behavior and societal responses during times of crisis.

The Covid-19 pandemic, although less severe, bears numerous similarities to London’s fictional “scarlet plague,” especially in its early stages.

The novel coronavirus vividly illustrated the rapidity with which pathogens can proliferate on a global scale in our interconnected world.

London’s work anticipated with accuracy the immense strain placed on healthcare systems worldwide. We witnessed overwhelmed hospitals, critical shortages of essential medical equipment such as ventilators, and healthcare professionals working under unprecedented pressure and personal risk.

In the period before the development and distribution of vaccines, society grappled with a pervasive uncertainty about how to effectively control the pandemic’s spread. This uncertainty led to the implementation of extreme measures, including widespread lockdowns, which echoed the drastic actions taken in London’s narrative.

Many individuals experienced a degree of isolation and fear reminiscent of London’s characters, albeit to a lesser extent.

I wasn’t scared. I had been exposed to the contagion and already considered myself dead. What struck me wasn’t this, but a feeling of tremendous depression. Everything had stopped. It seemed like the end of the world, of my world.

The pandemic brought to the forefront both the best and worst aspects of human nature, revealing a complex interplay of solidarity and self-interest.

Yet, even in despair, men were men. We fought, loved, cried, as we did before. The plague could not take away who we were.

While our society did not descend into the barbarism depicted in “The Scarlet Plague” – thanks in large part to successful epidemic control measures and scientific advancements – the crisis nonetheless exposed vulnerabilities in our social fabric and tested the resilience of our institutions.

Messages

The work imparts several messages that remain profoundly relevant in our current times:

- We cannot predict the emergence of new pathogens responsible for epidemic diseases, which can spread rapidly. Therefore, health organizations must be prepared to manage unforeseen situations with adequate reserves of personnel, equipment, and knowledge. Efficient healthcare systems are crucial not only for combating diseases but also for maintaining social cohesion by supporting populations during crises.

- It is vital to preserve, share, and document medical progress. Training, dissemination, and global access to medical knowledge must be guaranteed even in the face of catastrophic events. The loss of such knowledge would make any disaster even more devastating.

- Panic and disorganization during catastrophic and unforeseen events must be avoided. The healthcare sector, as well as other social organizations, must be prepared—both logistically and psychologically—to face these challenges.

Civilization is a thin veil. And without it, we have returned to what we once were, before we learned to govern ourselves, before we invented laws and moral principles.

Images from Wikimedia Commons