Clinical studies are categorized into several distinct groups, each possessing unique characteristics, methodologies, and inherent limitations. These categories are designed to address different research questions and scenarios in the medical field.

The primary classifications of clinical studies are as follows:

- Observational studies (also known as non-experimental studies) involve researchers observing and collecting data without intervening in the study subjects’ normal routines or treatments.

- Experimental studies: researchers actively manipulate variables and assign participants to different groups to test specific hypotheses under controlled conditions.

- Quasi-experimental studies: these share elements of both observational and experimental studies, where researchers may introduce interventions but lack full control over the assignment of participants to groups.

Observational studies (non-experimental)

Observational studies are research approaches where the investigator does not actively intervene but instead observes patients under specific conditions.

Subtypes of observational studies include:

- Cohort studies: researchers observe two groups of patients (cohorts)—those exposed and those not exposed to a factor—to evaluate its effect.

- Case-control studies: researchers compare patients with specific conditions (cases) to those without these conditions (controls).

- Cross-sectional studies: these examine the prevalence of a disease or condition at a particular point in time within a defined population.

A classic example of a cohort study is the renowned Framingham Heart Study, which tracked 5,000 participants to identify cardiovascular risk factors:

Kannel, W. B., Dawber, T. R., Kagan, A., Revotskie, N., Stokes, J. (1961). “Factors of Risk in the Development of Coronary Heart Disease—Six-Year Follow-up Experience.” Annals of Internal Medicine, 55(1), 33-50.

A case-control study examined the potential link between coffee and tea consumption and pancreatic cancer, ultimately finding no significant association:

Mack, T. M., Yu, M. C., Hanisch, R., Henderson, B. E. (1986). “Pancreas Cancer and Coffee and Tea Consumption.” Cancer Research, 46(9), 4800-4804.

An example of a cross-sectional study is one that assessed the prevalence of hypertension in the adult U.S. population:

Ostchega Y, Hughes JP, Terry A, Fakhouri TH, Miller I. Abdominal obesity, body mass index, and hypertension in US adults: NHANES 2007-2010. American Journal of Hypertension. 2012 Dec;25(12):1271-1278. DOI: 10.1038/ajh.2012.120

Experimental studies

In experimental studies, researchers actively intervene by modifying a variable (for example, administering a drug) and observe its effects. These studies are divided into three main types:

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs): subjects are randomly assigned to treatment or control groups.

- Crossover studies: Participants receive different treatments in sequence, acting as both cases and controls.

- Non-inferiority studies: a new treatment is compared to an existing standard of care to demonstrate that it is not inferior.

An example of an experimental study examined the effects of low-dose aspirin administration in an elderly population:

McNeil, J. J., Wolfe, R., Woods, R. L., et al. (2018). “Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly.” New England Journal of Medicine, 379(16), 1509-1518.

Quasi-experimental studies

Quasi-experimental studies have a design similar to experimental studies but lack randomization. They include:

- Studies with non-randomized treatment-control groups

- Studies that measure an outcome before and after an intervention in a single group

A quasi-experimental study evaluated the effectiveness of measures to prevent hospital-acquired infections by comparing outcomes before and after their implementation:

Hugonnet, S., Perneger, T. V., Pittet, D. (2002). “Effect of an Infection Control Program on the Prevalence of Nosocomial Infections in a Hospital: A Quasi-Experimental Study.” Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 23(1), 39-47

Other important study types include systematic reviews and meta-analyses—which synthesize existing studies to develop an overall estimate of an intervention’s effect—and diagnostic and prognostic studies. The latter evaluate the accuracy of diagnostic tests or develop models to predict patient outcomes.

The key distinction between experimental studies and other types lies in the randomization of patients or groups. In experimental studies, researchers randomly assign participants to different conditions to minimize bias and enhance validity. Other study types do not employ this randomization process.

Another crucial classification of clinical studies relates to how data are analyzed within or across groups. These analyses can be categorized as within-group, between-group, or mixed comparisons.

Within-group studies

Within-group studies examine variations that occur within the same group of participants. This approach is used when measuring certain conditions at different times in the same individuals, such as in repeated measures or cross-over studies.

Between-group studies

Between-group studies investigate variations that occur between different groups. These groups may receive different treatments, or one group may serve as an untreated control. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies are examples of this category.

Combined within-group and between-group studies

These studies blend both approaches, comparing two or more groups at different time points. Examples include repeated measures studies with multiple groups and cross-over studies.

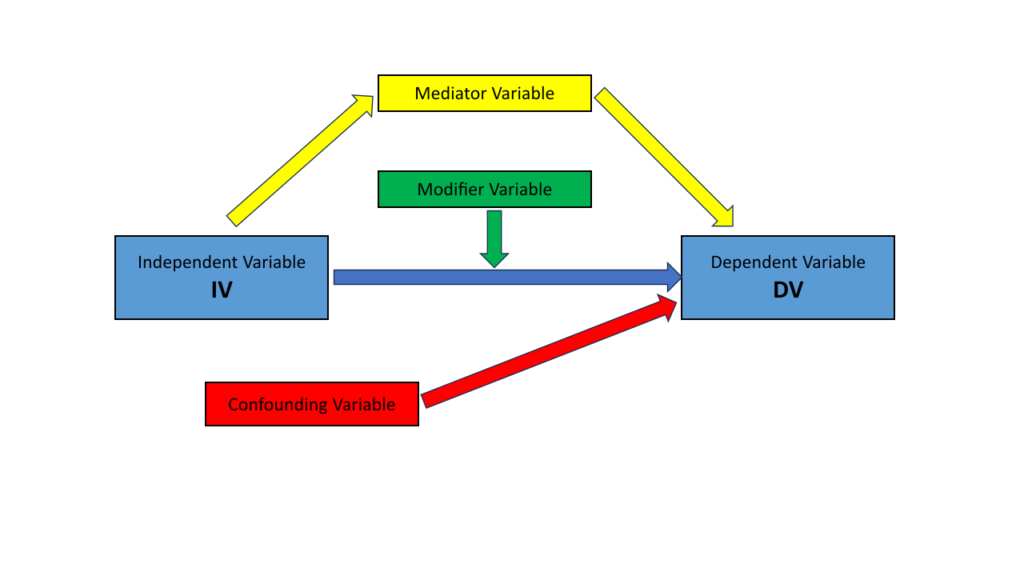

While not all studies directly investigate the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable, this relationship is fundamental in many research designs, particularly in experimental studies.

Independent Variable (IV): this is the variable that researchers manipulate or modify to observe its effect on another variable. In clinical research, it often represents a treatment, exposure, or intervention—such as a drug, therapy type, or behavioral change.

Dependent Variable (DV): this is the variable of interest presumed to be influenced by the independent variable. In clinical contexts, it typically represents an outcome like symptom reduction, survival rate, or quality of life improvement.

Beyond the IV and DV, researchers must consider several other variable types:

Confounding Variables: These external variables correlate with both the IV and DV. Their presence can lead to incorrect conclusions about the IV-DV relationship.

Effect Modifiers: These variables, while not confounding, alter the effect of the IV on the DV. For instance, a drug’s effectiveness might vary based on the patient’s gender.

Mediators: These variables are influenced by the IV and, in turn, influence the DV. They form part of the causal pathway between the IV and DV.