The Author

Albert Camus (1913–1960) was a French writer-philosopher and a key figure in existentialism.

Born in Mondovi, Algeria, Camus began his philosophy studies in Algiers. He later moved to Paris where, during World War II, he actively participated in the resistance against Nazi occupation. His most renowned novel is “The Stranger.” In 1957, Camus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

“The Plague”

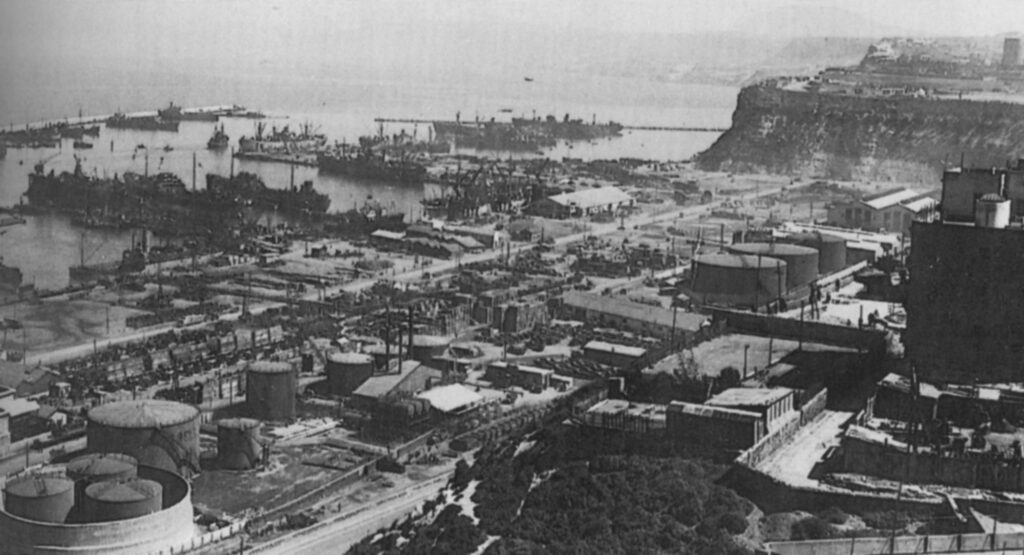

The novel is set in the Algerian city of Oran and chronicles a sudden plague epidemic that ravages the city.

Dr. Rieux serves as both narrator and protagonist, presenting the story as a firsthand account of the events.

Dr. Rieux, too, stood up. He was of medium height, broad-shouldered, and square-set. The brisk and energetic movements of his head, with its dark, steady eyes and firm mouth, suggested a man who was tenacious in purpose. His manner was direct, and he had a certain geniality of expression which never forsook him, even in his moments of irritability.

The narrative begins with the ominous discovery of dead rats—a warning sign overlooked by both authorities and citizens.

But what had happened in the last few days was quite out of the ordinary and, to his thinking, disquieting. For one thing, it was a fact that in this metropolis rodents were quite out of place, yet here they were, each day bringing in its train several hundred fresh rats, swept out of cellars and attics, to die in the open.”

Only when patients exhibiting high fever, swollen lymph nodes, and sudden deaths emerge does the diagnosis of bubonic plague send the population into panic.

Authorities place the city under strict quarantine, isolating it from the outside world. This isolation prevents communication even between family members, creating an extremely traumatic experience for the populace.

Rieux was astonished to find how easy it was to stop thinking clearly, how easy it was to lapse into a dream-like state where things happened of their own accord. In this state men could think of nothing but ‘the plague.’ All day they were caught up in an unbroken stream of rumors and alarms, one succeeding another.

As the infection spreads, the population’s reactions vary widely, ranging from apathy to moments of profound solidarity.

After several months, the epidemic begins to wane. Many have perished, and the survivors are deeply scarred by the experience. Dr. Rieux reflects that this event serves as a stark reminder of humanity’s enduring vulnerability.

The Novel from a Medical History Perspective

The novel transports us to the world in the middle of 20th-century medicine, depicting both its capacity to respond to disease outbreaks and the public’s perception of medical practices during that era.

Key aspects of the novel from a medical history perspective:

- Response to the epidemic: Initially underestimated, authorities soon impose strict isolation and quarantine measures. This mirrors historical responses to epidemics, as limited therapeutic and preventive capabilities made these the primary public health measures available.

- Therapeutic capacity: Dr. Rieux’s treatments are largely palliative and ineffective, reflecting medicine’s powerlessness against such infectious diseases before the advent of antibiotics and vaccines.

- Medical ethics: Dr. Rieux embodies a new portrayal of doctors, contrasting with previous centuries. Rather than a self-interested figure exploiting popular credulity and serving only the elite, he’s a people’s doctor who disregards social status and offers his limited abilities to all patients equally.

His profession required him to keep away from abstractions. ‘Only one idea was clear in his mind: that he was here to attend to the sick. And he had resolved to do that without a moment’s deflection. That, too, was a beginning. But it was no more than a beginning.

For who would dare to assert that eternal happiness can compensate for a single moment’s human suffering? Rieux had heard a mother crying for her dead child, and that cry remained with him… His job was to attend to them, to put his professionalism at the service of those who suffered, without questioning whether it was worth it or not.

Rieux said he knew the plague had cost him the power of emotion, and even the faculty of loving someone. Only love and duty made men endure their pain.

The work also reveals that disease, particularly the plague, was often perceived as divine retribution for collective sins. This view persisted for a long time, despite medical advancements.

Rieux knew now that the plague was here and that he must do his best to fight it. He remembered a phrase of his friend Tarrou: ‘Each of us has the plague within him; no one, no one on earth is free from it. And I know, too, that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him.

Furthermore, it highlights a growing sense of solidarity among the afflicted populations and demonstrates how the epidemic catalyzed efforts to strengthen and better organize healthcare structures.

Dr. Rieux resolved to keep silent and stay in the fight… He knew that the tale he had to tell could not be one of final victory. It could only be the record of what had to be done, and what, no doubt, would have to be done again in the never-ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaught.

This work holds significant importance from a medical history perspective. It serves as a powerful reminder of society’s vulnerability to epidemics, even in the face of advancing medical knowledge. The novel emphasizes the critical necessity for unwavering medical ethics, particularly during times of crisis when ethical boundaries may be tested. It vividly highlights the paramount importance of strengthening control and prevention measures in public health systems, demonstrating how these can make a substantial difference in managing outbreaks. Furthermore, the narrative underscores the invaluable lessons that can be extracted from past events, emphasizing how this historical knowledge can be utilized to better prepare for and respond to inevitable future outbreaks.

There is, however, a second layer of interpretation that uses medicine as a metaphor for France’s political situation during the Nazi occupation.

This reading highlights how the “disease,” with its ever-present destructive force, can be seen as a metaphor for the Nazism oppressing France at that time.

Dr. Rieux, in this context, becomes a symbol of resistance against this metaphorical plague. He confronts it as he does the literal plague in the novel: organizing responses, aiding the suffering, and persevering in his actions—even while aware of his limited power to combat the “infection.”

The quarantine and isolation of Oran can be interpreted as a reference to the invasive and oppressive control the occupiers imposed on the population.

Lastly, the initial underestimation that allowed the contagion to spread, followed by the resolve to learn from these events, mirrors the determination to be better prepared when the metaphorical bacillus—which can never be fully defeated—inevitably returns.

Through its compelling storytelling, “The Plague” not only entertains but also educates, leaving readers with a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between medicine, society, and human nature during times of widespread illness.

Images from Wikimedia Commons